Commissioned by the National Symphony Orchestra of Colombia, “Espíritu de Pájaro” is dedicated to Colombian indigenous groups and is inspired by poems from Hugo Jamioy (Camëntsá), Fredy Chikangana (Yanacona), and Vito Apüshana (Wayuu). The title of the work itself is taken from the poem “Espíritu de Pájaro” by Fredy Chikangana.

During the research for composing this work, I read many poems written by Colombian indigenous poets, most of them available in anthologies published by the Ministry of Culture of Colombia, among others. As I delved into the symbols and images I found in the reading, I understood that many of these poems had been composed in the native languages of their poets and that, for this reason, what I was reading might potentially have lost some of its meaning in the translation to Spanish. Even so, the beauty and sharpness of their message were undeniable and clearly perceived. Thanks to these images and my interpretation of their message, I built my own anthology of poems, grouping them into topics that eventually became the source for the composition of the scenes in this work. These scenes begin with an indigenous cosmogony, followed by a narration of life before the conquest, passing through violence and subordination, oblivion, the struggle for dignity, and ending in a movement dedicated to hope and reconciliation in present-day Colombia.

1. origen: Yunari

Inspired by the cosmogony of the Ette Ennaka people of the Magdalena region in Colombia, this is the story of the origin of the world and the cycles of life. Yunari is mother earth, the middle earth. “The streams are her veins and the waters are her blood. On her back and on her chest are the Ette.” New generations come from the land above. The land below, which supports the middle earth, is the dark land beneath which there is nothing. Each generation of the Ette ends when the earth is destroyed by wars and violence until a new generation replaces them. The current world is the fourth and penultimate generation. After the next generation, there will be no more violence or death because it will be the end.

This text is taken from the transcription of “El Mundo” narrated by Carlos Sánchez Purusu Takiassu Yaau, published in “El Sol babea jugo de piña: Anthology of Indigenous Literature of the Atlantic, the Pacific and the Perijá Mountain Range,” Miguel Rocha Vivas, Ministry of Culture, 2010.

2. Tierra, Yagé, y Minga

This movement flows seamlessly from the ‘Origen,’ opening with a thunderstorm that softens into gentle rain. Under this rain, ‘Tierra’ unfolds—a celebration of the work of the land. The dance embodies the jubilation of life and their intimate connection with Mother Earth. This central theme is expressed through a slow pasillo, a Colombian folk dance, which reappears only in the final movement.

As the tempo gradually intensifies, a powerful bass drum strike heralds the ‘Yagé’ scene. Yagé, or ayahuasca, represents a journey to the otherworld, described by Jamioy as a realm ‘where all truths rest, where nothing can be hidden.’ This segment is a visceral, hallucinatory experience. The persistent heartbeat of the bass drum guides the trance, eventually subsiding as the music gently returns to earthly realms.

The movement concludes with ‘Minga,’ inspired by Chikangana’s poem. This scene portrays collective agricultural labor in its full complexity—encompassing struggle, exhaustion, and hardship, but also the profound sense of uplift found in communal work. It serves as a more intricate reprise of the ‘Tierra’ theme, now enriched by the intervening mystical experience.

Poems: “La Tierra” (Chikangana), “En la Tierra” (Jamioy), “Yagé I” (Jamioy), “Minga” (Chikangana)

3. Tierra Luminosa (Luminous Earth)

This dance portrays life before the conquest, depicting the cultural richness of indigenous peoples and their unique perception of the world and life prior to the arrival of the Spanish. The movement celebrates the multifaceted dimensions of indigenous life: language, music, history, community, and connection to the land. It honors what generations built over thousands of years—a legacy that, despite the violence of conquest and colonization, still survives in contemporary indigenous communities.

Poems: “Gota de la Noche,” “Del Fuego,” and “Gente” by Chikangana, and “Danza” by Apüshana.

4. Conquest

This movement portrays the brutal impact of conquest: physical violence, death, and the devastation of indigenous lands and cultural heritage. It depicts the disruption of life, the forced exile of survivors, and the imposition of foreign values. The music incorporates a military march, symbolizing the relentless advance of conquest that obliterates everything in its path. Survivors witness the violent theft of their entire world, experiencing what Chikangana describes in one of his poems as the “pain of being captive in [their] own land.

Poems: “Muerte,” “Del Vacío,” “El Alto Vuelo del Quintín Lame” by Chikangana.

5. Lenguas (Tongues)

This scene begins without interruption after the previous movement. “Lenguas” represents the void left to the first inhabitants of our territory by the forced imposition of foreign language, values, and culture, along with the destruction of their culture and legacy, one of the most devastating consequences of the conquest.

The movement was inspired by the poems “Buscándome,” “Solo a ese lugar debes ir,” “Analfabetas,” ”En qué lengua,” and “Esta geografía,” by Jamioy. The feeling of this scene also reflects ideas from the concept of “violencia de la colonización alfabética” (The erasure of native voices through colonial ‘literacy’) described by Miguel Rocha Vivas in his book “Mingas de la Palabra” and from the fragment of “The Autumn of the Patriarch” by García Márquez, which uses the text of the chronicle of Columbus’s first voyage and rewrites it in the form of parody from the point of view of the indigenous native.

6. Puñado de Tierra (Fistful of Earth)

The character of this movement represents the oppression and oblivion that current Colombian indigenous groups continue to suffer as a consequence of violence and their exile. The last part of the movement is a march, very different from the march of conquest. It’s not a military march but a walk full of heartbreak representing the indigenous protest marches of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Poems: “Puñado de Tierra,” “Minga,” “Todo está Dicho,” by Chikangana and “Esta Soledad” by Jamioy.

7. Espíritu de Pájaro

The title of the movement alludes to the lightness and freedom of the bird flying as a metaphor for the free and hopeful spirit of the liberated indigenous people reunited with their land and culture. The movement takes its title from the poem of the same name by Fredy Chikangana, a poem that alludes to music of the earth and the hopeful journey that collectively transcends suffering and struggle.

8. Finale: Todavía Tenemos Vida en esta Tierra (We Still Have Life in This Land)

The final movement is musically a coda of the ballet that retells the story through variation and development of melodic and rhythmic elements from previous scenes. The music is recognizable but its harmony, orchestration, and character are transformed expressing a more hopeful outcome, as a symbol of reconciliation.

Poems: “Todavía Tenemos Vida en Esta Tierra,” “La Cabeza,” “Soy Cantor” by Chikangana; “Gente” by Apüshana; and “Camina con tu Pueblo” by Jamioy.

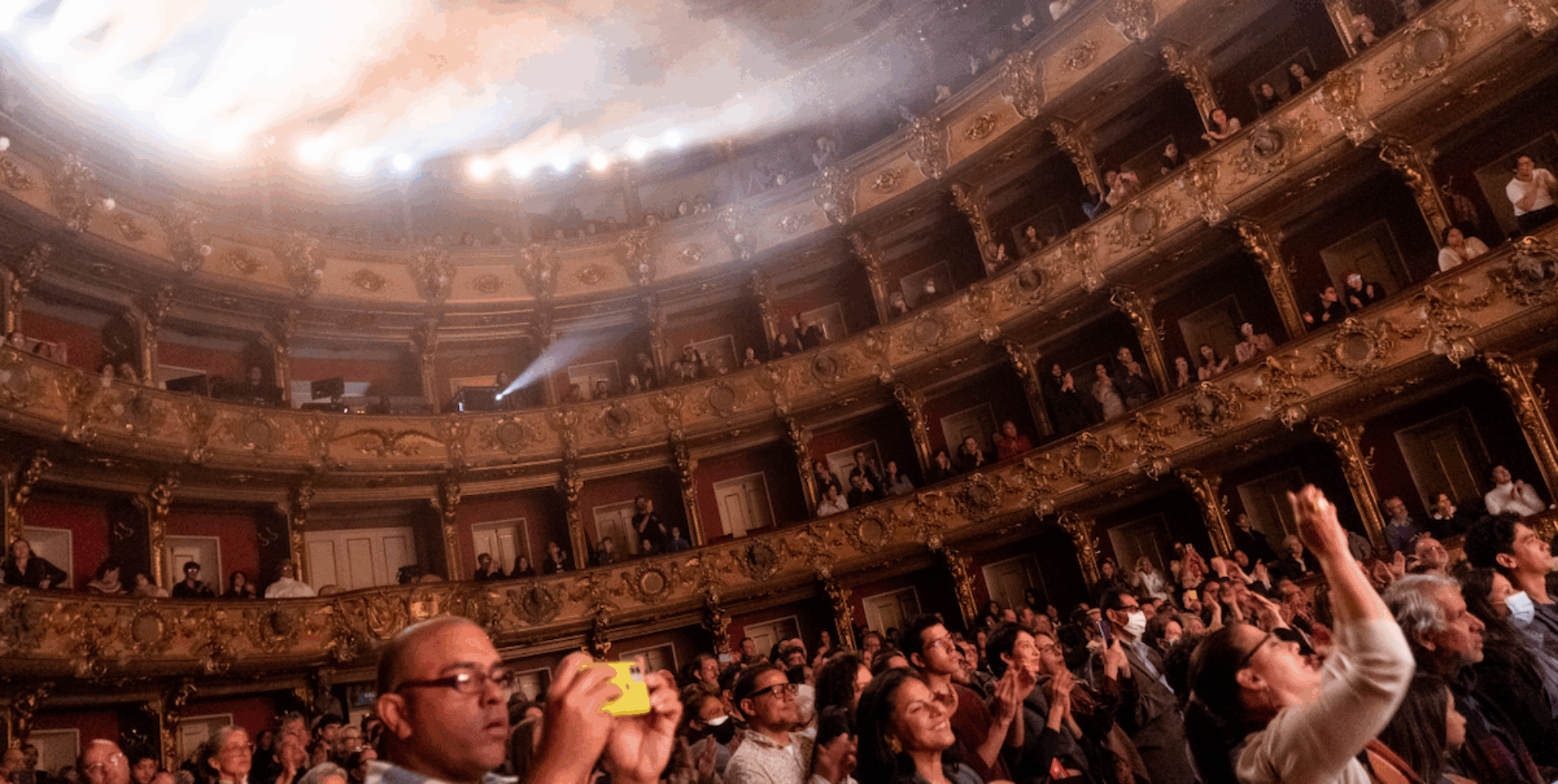

Espíritu de Pájaro was premiered in Bogotá, Colombia, on November 4, 2022 by the Orquesta Sinfónica Nacional de Colombia, Juan Felipe Molano, conductor and the Colegio del Cuerpo dance company, with choreography by Álvaro Restrepo.